Udaipur 2020. Studio trip to Udaipur to study vernacular architecture of Rajasthan.

Written by Aatman Modi.

Growing up in an architect’s home meant that architecture wasn’t something I chose—it was always there. Our house was also our design office, where I would come home from school to find designers pouring over drawings, building models, and sketching intricate plans. I was that overly curious kid who asked far too many questions, much to the amusement (and occasional exhaustion) of the designers around me. I was fascinated with how a simple sketch could turn into a fully realized space, how my parents and their team would decide where to place a window based on sunlight, wind direction, and comfort, or why certain materials worked better in one region but not another. Our vacations weren’t to beaches or theme parks; they were spent exploring historical architecture, forts, and cities, trying to understand how buildings stood the test of time. These experiences shaped how I viewed architecture— not just as a profession but as something that fundamentally impacts everyone’s daily life.

As I moved to the U.S. and started working at West Work, I decided to pursue my Certified Passive House Consultant (CPHC) certification, I found it ironic that Passive House principles were often framed as a cutting-edge solution when, in many ways, they had already existed for centuries in traditional Indian architecture. The more I learned about passive heating and cooling strategies, the more I saw overlaps between modern energy modeling and the climate-responsive designs of historical Indian structures. When I started working with WUFI modeling, I was able to quantify the impact of design choices in a way that proved what I had intuitively observed growing up. Seeing hard data back up centuries-old vernacular architecture reinforced how much knowledge had been lost in favor of modern, high-energy building practices.

The Origins and Sustainability Logic of Vastu

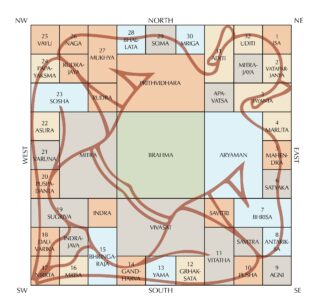

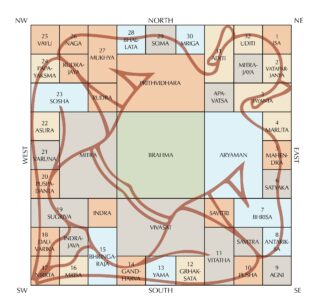

Vastu Shastra’s origins are deeply rooted in mythology and cosmic balance. Legend tells of a great cosmic battle in which a powerful demon had to be restrained by Brahma and 45 deities, forming the foundation of Vastu Purusha Mandala, a sacred grid used in traditional design. While mystical in its storytelling, this framework had a very practical function—it ensured that buildings were designed in harmony with their environment.

The Vastu Purusha is divided into a 9×9 grid with 45 gods holding the demon down.

Vastu’s principles were developed through empirical observation of climate, materials, and spatial organization. Master bedrooms were placed in the southwest to stay cooler during the night when they were occupied, water bodies were placed in the northeast for evaporative cooling, and courtyards were incorporated for cross-ventilation and passive temperature regulation. These strategies were not arbitrary; they were refinements of climate-adaptive architecture that evolved over centuries.

But Vastu is not a rigid set of rules—it has always been an adaptable framework. No home is ever 100 percent Vastu-compliant, as real-world constraints require balancing tradition with practicality. This flexibility is what makes it so relevant today, as we seek ways to merge historical wisdom with modern sustainability metrics.

A framework derived from the 9×9 grid and positions of deities.

Passive House: A Scientific Approach to Energy Efficiency

While Vastu relied on empirical knowledge, Passive House takes a performance-driven approach to sustainability. Developed in cold European climates, Passive House focuses on minimizing energy loss and maximizing thermal comfort. At its core, it prioritizes airtight construction to prevent unwanted heat loss or gain, superinsulation to reduce energy dependency, and high-performance windows and shading strategies to control solar exposure. Additionally, Passive House eliminates thermal bridges, weak points in the building envelope where energy loss can occur. Finally, mechanical ventilation with heat recovery ensures consistent fresh air circulation while maintaining indoor temperature stability.

Although originally designed for colder climates, Passive House principles have been successfully adapted for warm regions, incorporating elements such as shading, night flushing, and moisture management. This adaptability raises an important question: How do Passive House strategies compare with traditional Indian architecture, and what can they learn from each other?

Comparing Ventilation, Materials, and Climate Adaptation

One of the key differences between Passive House and Vastu is their approach to ventilation. Passive House prioritizes airtightness, relying on controlled mechanical ventilation to manage airflow and prevent energy loss. Vastu, on the other hand, embraces natural ventilation, using courtyards, perforated walls, and shaded verandahs to facilitate passive cooling. In hot and humid climates, excessive airtightness can lead to moisture retention issues, making Vastu’s open-air approach a valuable complement.

Another major distinction is material selection. Passive House buildings rely on engineered insulation and high-performance construction to maintain thermal efficiency, while Vastu-built structures use high thermal mass materials like brick, lime, and stone, which stabilize indoor temperatures naturally. In our own work in India, we are currently experimenting with building a home in India using lime, similar to historical forts and havelis, and modeling its performance in WUFI to understand energy efficiency and thermal regulation.

In terms of climate-specific adaptation, Passive House uses energy modeling to mathematically optimize designs for different regions, whereas Vastu evolved more organically based on regional conditions. For example, buildings in Rajasthan feature thick stone walls and internal courtyards for heat mitigation, while homes in Kerala have elevated wooden structures and sloped roofs to address humidity and heavy rainfall.

The Padmanabhapuram Palace, one of the oldest palaces in India. It showcases sloped roofs and a series of courtyards to maintain thermal comfort.

Courtyards in hot and dry climate of Rajasthan feature openings to let hot air escape. Along with thick stone walls adding to the mass of wall, temperature inside the structure is regulated.

Can Passive House and Vastu Work Together?

Despite their differences, Passive House and Vastu share the common goal of creating highly efficient, comfortable, and sustainable buildings. A hybrid approach could leverage Passive House’s precision with Vastu’s adaptability, creating designs that are both high-performing and culturally contextual.

A Passive House designed with Vastu principles could optimize mechanical ventilation while still prioritizing cross-ventilation, integrating insulation while incorporating thermal mass, and using modern energy modeling to validate traditional cooling techniques. Similarly, Passive House buildings in warm climates could benefit from Vastu-inspired spatial zoning, reducing cooling loads while enhancing occupant comfort.

The Future of Climate-Responsive Architecture

For me, this journey isn’t just about understanding these systems academically—it’s about applying them to real-world projects. My work has reinforced that modern sustainability is often about rediscovering what we already knew—that the best buildings are deeply rooted in place, history, and an understanding of how people interact with their environment. By bringing together Vastu’s time-tested principles and Passive House’s scientific rigor, we can move toward a future where architecture is not only efficient but also deeply connected to cultural and environmental realities.