Written by Aatman Modi, Graphics by Yasmin Morais Torquato.

The United Nations’ Environment Programme, the UN’s commission to support the implementation of global environmental obligations, published a 2023 report called Building Materials and Climate: Constructing A New Future, which indicated that the building and construction sector is responsible for an astonishing 37% of global emissions. Since 1975, when the term “global warming” first appeared in the news, engineering, and architecture have been linked to the warming of the planet via our collective role as the designers of infrastructure and buildings. In the ensuing years, environmental activism, bipartisan legislation, and social pressures have spotlighted human-centric resource consumption.

As part of these conversations, LEED Certification emerged as a tool for designers and building owners to make more sustainable buildings. Other systemic approaches followed, including EnergyStar, Living Building Challenge, and Passive House. Which certification to choose?

The United States Green Building Council (USGBC) was formed in 1993. Five years later, the council launched Leadership in Environmental and Energy Design, commonly called LEED. In Architecture, Engineering, and Construction, LEED has been transformative to a common understanding of the impact of buildings. While it has evolved – there have been seven iterations with the current version LEED 4.1 under review – the principles remain intact. There are seven core categories: sustainable sites, water efficiency, energy and atmosphere, materials and resources, indoor environmental quality, innovation, and regional priority. To illustrate the program’s impact, in 2018 USGBC was able to demonstrate that over a million square feet of construction were certified under LEED daily (USGBC, 2018).

A core reason for LEED’s popularity is its checklist approach that rewards applicants with medals for maximizing points. Like Olympic athletes, buildings strive for a maximum of 110 points and are rewarded – commensurate with achievement – with certification, silver, gold, or platinum medals. LEED has removed the mystique surrounding green design. Irrespective of size, all construction projects require a stakeholder team (i.e. Owners, designers, contractors, and public officials.) to use a common scorecard to evaluate a project. While it is not easy to achieve LEED platinum status, the requirements and benefits are generally easily understood. However, there are limitations. LEED is a conceptual framework that does not quantify carbon impact. As the goals for reducing global emissions become increasingly data-driven, USGBC’s program has two common critiques:

(1) The LEED system can be manipulated.

(2) The LEED checklist does not account for regional context.

As to the first, one could potentially achieve LEED platinum by meeting ASHRAE 90.1, the standard that sets minimum requirements for energy-efficient design in most building types but still has a fossil fuel source for heating and cooling. Furthermore, the building may be under no obligation to demonstrate superior post-occupancy performance. In other words, some LEED-certified buildings may not achieve the energy efficiency levels anticipated; there is less predictability in specific energy performance as no computational modeling is required in advance of earning points.

A second criticism of LEED is that it is too broad. While LEED covers many aspects of sustainability, its energy efficiency standards are not sufficiently adjusted across climate zones. This may be temporary as Regional Priority (RP) credits in recent versions encourage project teams to seek points that address the most critical environmental issues in their communities. LEED does not however account for differences in microclimates (e.g. challenges of heat island effect in Downtown Boston vs rural Maine.) Various climate zones across the USA use the same checklist.

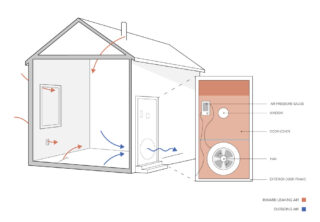

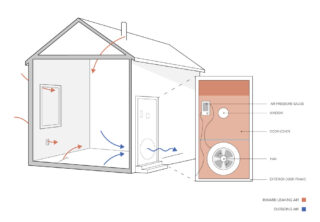

Passive House is like LEED in that it is a certification program that municipalities are beginning to adopt, but narrower in its focus on minimizing energy use by using a highly insulated building envelope. Originating in Germany in the early 1970s, Passivhaus standards were adopted around 2000 as a rigorous standard for building envelope design. In 2007, the U.S. Passive House Institute (PHIUS) was formed. Core concepts of Passive House include reducing thermal bridging, ensuring airtightness, optimizing window placement and quality, incorporating balanced ventilation, and maximizing solar gain. The standard’s focus is both energy use and enhanced indoor comfort.

Passive House provides site- and building-specific heating and cooling targets and site energy use in qualifiable metrics.

Passive House arguably has a steeper learning curve than LEED. To become a Certified Passive House consultant or Builder, one is required to pass through a set of classes that not only educate on the principles of Passive House but also train professionals to simulate building performance. A WUFI energy model predicts how buildings use energy and handle heat and moisture. To put it into perspective, the study plan available on LEED’s website, calls for a four-week schedule, allocating 3-5 hours a day, which is 84-140 hours. PHIUS intends for its certification course, which includes self-guided learning, live sessions, and a two-part exam, to be completed in 12 months. There are currently around 1700 PHIUS-certified consultants in the country. More than 200,000 people have passed the LEED exam.

Passive House may also be more expensive than LEED to implement. Although it may be only 3.5% more expensive to construct a Passive House building as compared to a traditional home (MultiFamilyDive, 2023), the administrative procedures can be tedious and time-consuming, requiring additional consultants and increasing project fees. The process starts at the Design Development stage and continues until the occupancy permit is issued. For certification, architects are required to submit detailed paperwork, including an energy model. PHIUS requires applicants to pursue additional sister certifications like EPA Indoor Air Plus, DOE Zero Energy Ready Home, and EPA Energy Star Multifamily, which also affects the timeline. For construction, the architect must meticulously detail all material transitions and corners. The contractors must have the technical knowledge of passive house construction to execute the details, without these efforts, achieving the air tightness target is unlikely. To confirm the achievement of the required air tightness (0.06 cfm), the building owner must arrange for a blower door test, which uses a powerful fan to pull air out of the house, thus identifying leaks and drafts.

Despite its challenges, Passive House certification has gained a foothold in building codes.

Massachusetts communities Cambridge, Somerville, and Boston have mandated that new multifamily construction over 12,000 sq. ft. must be Passive House Certified.

The City of Boston has added 4-6 million square feet of new construction every year since 2014 according to a Carbon Free Boston – Buildings Technical, and the boom continues.

A recent DOE report found that LEED-certified homes use 20-30% less energy than non-green homes. Another 2020 study by the Building Energy Exchange found that Passive House-certified buildings are up to 60-85% more efficient than a comparable conventional building, when compared to a 2009 IECC code-compliant building, depending on climate zone and building type. To increase the adaptability of Passive House, various incentives and tax breaks are being provided, as it is increasingly common knowledge that the implementation of Passive House principles would make a great dent in our carbon footprints.

Passive House and LEED are different certification systems, each with strengths. It would be unjust to say that one is superior to the other. But Passive House’s intense focus on minimizing energy use and the program’s predictable outcomes based on required modeling and testing give it an edge in forcing quantifiable progress. As the timeline for carbon reduction gets closer to 2030/2050 mandates, measured reductions in carbon consumption become increasingly appealing.